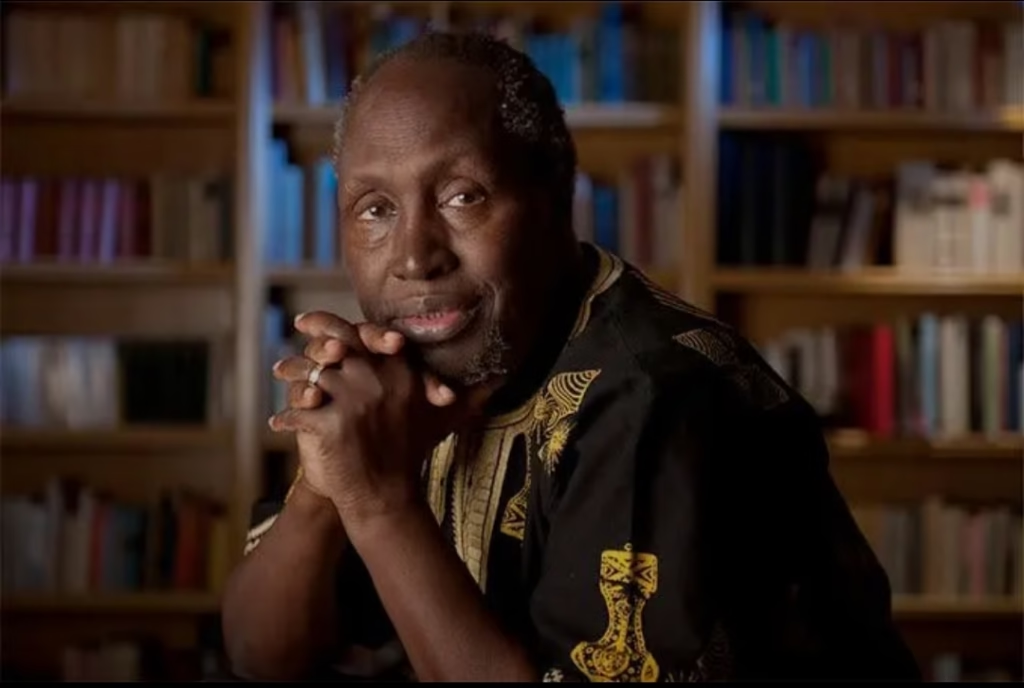

Africa has lost a giant, a legend, and a loud, unshakable voice of justice. But even in death, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o remains immortal not through monuments, medals, or government tributes, but through his words. He was a writer, yes but far more than that, he was a warrior. A rebel with a pen. A man who made language bleed, and literature roar.

From dusty village theatres to global lecture halls, Ngũgĩ challenged the powers that be. He tore apart the polished masks of African dictators, exposed the betrayal of the independence dream, and boldly confronted the new chains of mental colonization. His books were not just stories they were revolutions. And through them, he carved his name into the walls of resistance, where it will remain for generations to come.Now, as the continent mourns his passing on the evening of Thursday, May 29, 2025, we do not just say goodbye. We rise to honour the power of his voice, the weight of his truth, and the fire he sparked against bad governance, injustice, and colonial domination.

Truth-Teller in a Land of Lies

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was born in 1938 in Limuru, Kenya in a land caught between colonial chains and the rising hope of freedom. That tension shaped him. As a young man, he watched the brutality of British rule, the Mau Mau rebellion, and the betrayal of independence by African leaders who quickly replaced white masters with black oppressors.

In his early novels like “Weep Not, Child”, “The River Between”, and “A Grain of Wheat”, Ngũgĩ painted a vivid picture of a country fighting for freedom and then losing it again in the hands of its own people. While others glorified independence as a heroic success, Ngũgĩ boldly asked: What has really changed for the common person?

His stories were brutally honest. In “Petals of Blood”, he follows four characters from a rural village who become witnesses to greed, corruption, and betrayal in post-independence Kenya. The novel is a cry against the betrayal of the poor by the new African elite who mimic colonial brutality in black skin. The title itself is symbolic independence promised petals, but delivered blood.For Ngũgĩ, literature was never about escape. It was about exposure. He saw it as a weapon, a tool to awaken the oppressed, to shame the corrupt, and to build the dream that independence failed to deliver.

Arrested for a Play, Not a Gun

In 1977, Ngũgĩ did something revolutionary. He co-wrote “Ngaahika Ndeenda” (I Will Marry When I Want) a community theatre play performed by local villagers in Gikuyu, not English. It was raw, bold, and fearless. It condemned land grabbing, economic exploitation, and religious hypocrisy in the new Kenya. The audience was the poor. The target was the elite. And the impact? Explosive.

The government could not tolerate such truth. They responded the only way they knew how by arresting him. Ngũgĩ was detained without trial at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. He was locked up not for carrying weapons, but for carrying dangerous truth and telling it in a language the people understood.

But the prison could not silence him. It only sharpened his fire. Inside his cell, he began to write “Devil on the Cross”, using toilet paper as his notebook. It became a masterstroke of political satire. In it, the devils corrupt politicians, foreign capitalists, and greedy elites gather in a grotesque competition to show who has stolen the most from the people. The novel was hilarious, yes, but also devastating in its truth. It exposed the silent war on the poor, masked behind development slogans and aid packages.

Ngũgĩ’s arrest marked a turning point not just in his life, but in the history of African literature. He had declared, without apology, that writing is resistance.

The Final Battlefield

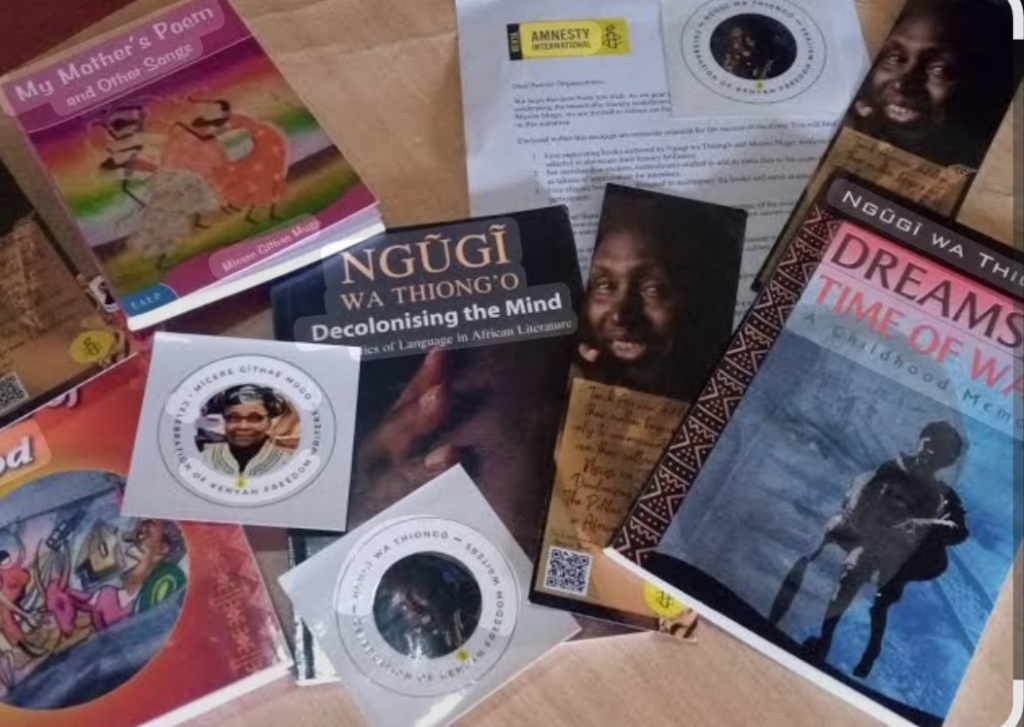

After prison, Ngũgĩ made a groundbreaking decision: he would no longer write in English. Instead, he embraced Gikuyu, the language of his people. It was a radical move that shocked many. But for Ngũgĩ, it was about reclaiming identity, memory, and freedom.

In his landmark work “Decolonising the Mind”, he argued that the most dangerous weapon of colonization was not the gun it was the erasure of African languages and the forced adoption of foreign ones. Language was how people thought, how they saw the world, how they connected to their past. Strip a people of their language, and you strip them of their soul.

By choosing Gikuyu, Ngũgĩ was refusing to think in the language of the colonizer. He wanted African children to read about themselves, in their own tongues, to know that their stories mattered without translation. He believed the liberation of Africa had to begin in the classroom with the stories we tell, the names we remember, and the words we choose.

This decision made him both a hero and a threat. He was now seen as a cultural rebel and soon, a political exile.

Exile Without Silence

After facing constant threats, Ngũgĩ fled Kenya in 1982. But exile did not dim his light. It made it burn brighter. From the U.S. and Europe, he continued to write, teach, and speak. He gave Africa a voice on the global stage one that was bold, unfiltered, and unforgettable.

In “Matigari”, he tells the story of a revolutionary who buries his guns, believing that peace has come only to realize the oppressors have never left. It’s a haunting tale of betrayal, echoing the frustration of millions of Africans who hoped for change but got more of the same. The novel was banned in Kenya before it was even officially released.

Years later, Ngũgĩ published “Wizard of the Crow”, a sweeping satire about a fictional African country ruled by an absurd dictator who believes himself divine. It’s witty, surreal, and deeply political. But beneath the comedy lies sharp truth: that African governance, hijacked by cult-like power, foreign dependence, and internal corruption, often becomes a theatre of madness.

A Legacy Carved in Fire

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s work has been translated into dozens of languages, studied in universities worldwide, and performed in theatres across continents. But his true power lies not in awards or applause it lies in how his words changed minds, ignited resistance, and gave the oppressed a voice.

He taught us that the fight for justice begins in the mind. That freedom means little if people cannot think freely, speak in their own languages, and tell their own truths. He warned us that post-colonial governments could become worse than their predecessors if they forgot the people. And he proved that a pen in the right hands can shake even the tallest thrones.

Rest Not in Peace, But in Power

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is gone, but he has not rested. His books still rise in protest. His plays still echo in village halls. His essays still whisper to young Africans: Don’t just read. Resist. Don’t just dream. Demand.

He did not wait for permission to speak. He did not kneel to power. He turned literature into a battlefield and emerged as one of the fiercest warriors Africa has ever known.

Rest in power, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

You lit a fire in our minds.

Now, it’s up to us to carry the torch forward.

The struggle continues. Just as you warned and just as you hoped.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s legacy is truly monumental, and his words continue to resonate deeply. His ability to challenge both colonial and post-colonial injustices through literature is nothing short of inspiring. It’s fascinating how he used his pen as a weapon, not just to tell stories, but to ignite revolutions. His works like “Petals of Blood” and “Weep Not, Child” are not just books; they are mirrors reflecting the harsh realities of society. I wonder, though, how much of his vision for Africa has been realized today? His critique of post-independence leaders still feels relevant, but has there been any progress? Ngũgĩ’s voice was a call to action—do you think his message is being carried forward by the new generation? His passing is a loss, but his words remain immortal. How can we ensure that his fight for justice and equality continues to inspire change?