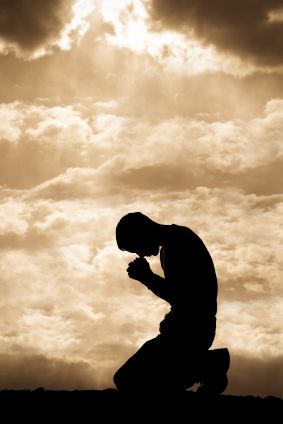

From a chapel pew comes a whisper. A clearing in the forest echoes with a chant. In silent meditation, a breath slows. The same yearning permeates all of them, despite the various settings and sounds. Humans have transcended themselves over centuries and cultures, influencing prayer not only through belief but also through memory, rhythm and place. It is important to pay close attention and realize that the sacred frequently speaks in multiple languages when comparing Christian prayer with indigenous invocation, chants and meditation.

Christian prayer is frequently word centered, particularly in its traditional forms. Through praise, confession, prayer and gratitude, it communicates with God. The Lord’s Prayer, recited across continents, serves as both a personal plea and a communal bond. Its structure is deliberate and the language is both intimate and reverent. Prayer here becomes conversation, with God addressed as a listener, responder and presence. Speech usually comes first, followed by silence.

In contrast, indigenous prayer frequently communicates with the world rather than above it. Invocation focuses on relationship rather than recitation. Mountains, ancestors, rivers and animals are not mere metaphors but active participants. Chants are repeated not to persuade a distant deity but to help the speaker connect with the rhythms of prayer. Traditional chants may express gratitude to the earth for providing bread, while Christian prayers may ask for it every day. One reaches outward the other upward.

Chants connect spirit and sound. Repetition serves as a gateway in both indigenous ceremonies and Christian monastic traditions. Repetition of a phrase releases the hold of distraction. The heart listens, the mind calms. Tribal songs and Gregorian chants may have different melodies but they both aim to transport the soul to places that words cannot. Here, prayer lingers, like incense in still air, rather than being hurried.

Meditation complicates the comparison even more. Silence itself is prayer in many Eastern influenced and indigenous practices. Silence turns into sacred discourse. The individual becomes attentive, observing breath, thought and sensation instead of speaking to God. This is echoed in some Christian traditions through contemplative prayer in which God is encountered in quiet presence rather than being named repeatedly. In a curious paradox, prayer can sometimes be the most powerful when it says nothing.

These practices appear distinct, even threatening, from a rhetorical standpoint. The land is named by one and God by another. While one seeks direction, another seeks harmony. Beneath the contrast, however, is a common human desire of connection. All forms of prayer, whether they are sung, spoken or silent, lean toward relationships with the self, the community and the divine.

Frequently, history rather than intention is what distinguishes these customs. Native prayers were framed as superstition and Christian prayer as truth during colonial encounters. However, comparison reveals something more truthful that the grammar of the sacred is not owned by any one culture. Prayer changes. It picks up new dialects. It dresses differently.

Ultimately, prayer in all cultures serves as a reminder that faith is a chorus rather than a monologue. We discover harmony rather than losing our voice when we listen outside of our traditions. It appears that the divine has always been bilingual.