As campaigns for the by-elections in different parts of the country gain momentum, the contests are emerging as more than simple cases of filling empty seats.

They will be a crucial test case for political parties, institutions, and the voters themselves. Anything but trivial political battles, the by-elections have now assumed a symbolic dress rehearsal semblance for the 2027 general election with implications far wider than the wards and constituencies at hand.

For the newly founded party of the former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, the Democratic Change Party (DCP), this will be the first big test of political brawn. Having made their entry in pageantry and with a promise to shake up the political establishment in Kenya, DCP now has to turn rhetoric into votes.

This is not so much about winning or losing seats, it is about proving relevance. If DCP manages to gain traction in these elections, it will gain acceptance as a credible alternative by the time 2027 arrives. If it does not succeed, critics will quickly dismiss it as yet another failed party in Kenya’s crowded political arena.

The ruling United Democratic Alliance (UDA) is also not safe from a daunting challenge. The by-elections will provide a test of popularity for the president and his party. The UDA was elected to office on a wave of populism and promise of economic renaissance, but much has changed since.

Rising living expenses, austerity, and growing public disillusionment have created enormous attention for the government. The by-elections will reveal whether UDA still enjoys the support it had in 2022 or cracks have already started appearing in its support base.

Victory would be interpreted as endorsement of the government agenda, but losses would give strength to critics who argue that the ruling party is losing grip on voters.

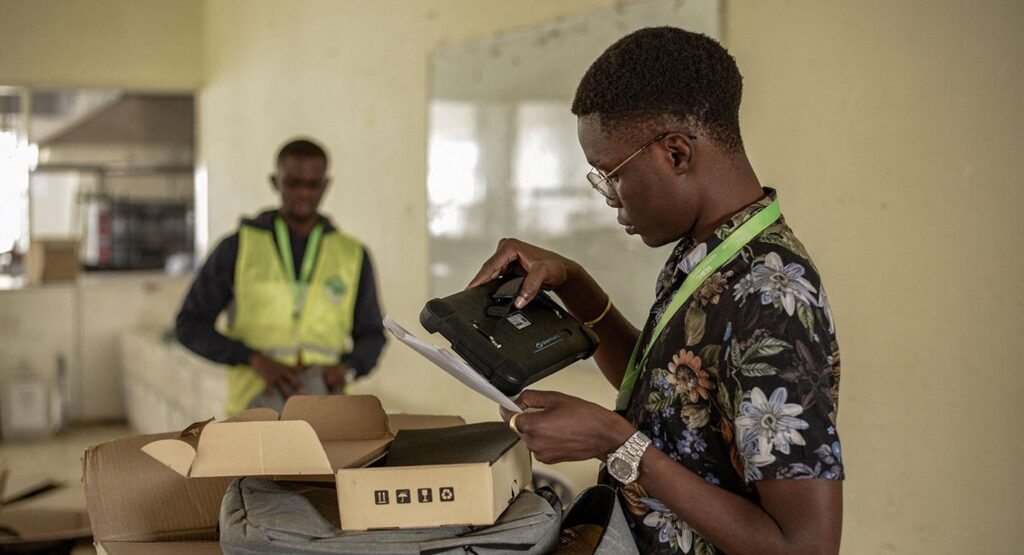

Afar the partisanship battles, the spotlight also heavily rests on the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). Reconstituted after weeks of political intrigue and uncertainty, the IEBC must now prove its competence, impartiality, and endurance. By-elections may have lower electorates than general elections, but the underlying reason is to test systems, procedures, and people’s trust.

Any mishap procedural, technological, or logistical will not only challenge the credibility of these by-elections, but also cast doubt on the commission’s ability to deliver a credible 2027 general election. For an organization that has been repeatedly accused of bias and inefficiency, the stakes could not be higher.

At the heart of it all, however, are the voters. In the wards and constituencies where vacancies exist, average Kenyans will walk to the ballot not just to choose leaders, but to make a political statement. Their votes will pulse the nation.

Does the citizenry still trust the ruling party to deliver? Are they ready to experiment with new political sets like DCP? Or are they disillusioned across the board, foreshadowing the sort of voter alienation that will reshape the broader election landscape in years to come? By-elections within a democratic environment give voters an opportunity to approve, disapprove, or demand change beyond the normal cycle of the general election.

These by-elections, therefore, must be viewed as being greater than simple administrative necessities. They are legitimacy and credibility tests, as well as a gauge of where Kenya’s politics is headed.

For DCP, it is survival and staying relevant. For the president and UDA, it is to sustain people’s confidence in them. For the IEBC, it is to restore confidence to carry out free and fair elections. And for the people, it is to alert the political class that sovereignty resides in the people’s will.

The results will not only fill vacant seats these will echo across the politics, setting stories, cohorts, and plans up to 2027. What happens in these little-known contests will, in large part, decide the direction of the battles ahead. Kenya’s democracy is once again at the crossroads, and these by-elections could well determine where it goes next.